Antique Mughal Silver Gilt Betel Pandan Tray, Turquoise Stones, India – 1750

Antique Mughal Silver Gilt Betel Pandan Tray, Turquoise Stones, India – 1750

£16,000.00

Description

This rare and beautiful antique Mughal silver gilt betel, or pandan, tray is of good size and has two handles. It is a superb example of 18th century Indo-Persian silverware which would have been used to hold the various ingredients needed to prepare a betel quid and to provide a surface for preparing the quid. This is an object of extremely high status which benefits from being inscribed with the name of its illustrious owner. The tray was likely made in Hyderabad.

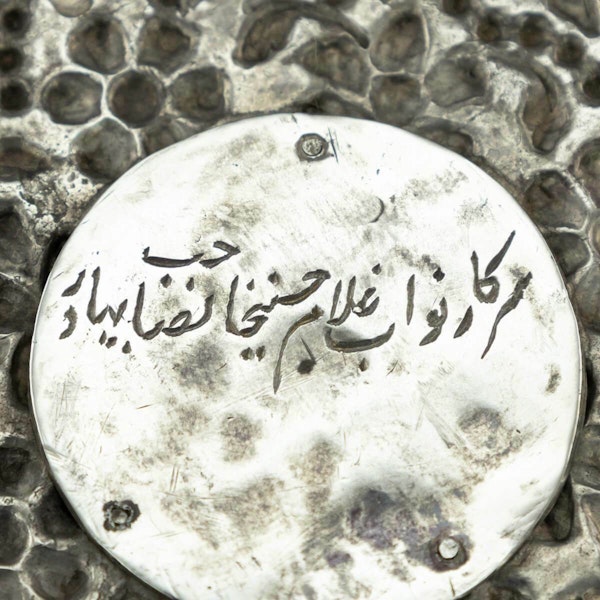

Written in Urdu, the name engraved on the central cartouche to the underside is, ‘Sardar Nawab Ghulam Hussein Khan Sab Bahadur’ and there is a picture of this inscription within the photos. Nawab was the title given to an Indian governor during the time of the Mogul empire and the title "Khan Bahadur" was conferred on Muslim subjects in recognition of public services rendered.

Ghulam is also known as Nawab sayyid Ghulam Muhammad Ali Khan I Bahadur, the second ruler of the Naqdi dyasty who twice became Nawab of Banganapelle (now known as Banaganapalli in the District of Andhra Pradesh). On his marriage, he was gifted the lands and rule of Chenchelimala. He ruled from 1783 to 1784 and again from 1789 to 1822. Banganapelle was a fief of the Mughal empire and later became a princely state of British India. Ghulam’s family were descended from Tahir Ali, younger son of the Grand Vizier to Shah Abbas II of Persia who migrated to India during the reign of Emperor Akhbar. His father and uncle had served as high ranking military officers under the Bijapur Sultans of the Deccan, transferring their allegiance to the Mughals after the Mughal conquest of the Deccan.

Ghulam Muhammad Ali was very young when his father died in 1783 and he became ruler (Jagirdar) under the guardianship of his Uncle. Within a year, following the invasion of Hyder Ali, the family were forced to flee north to Hyderabad and his reign ended. Ghulam entered service with the Nizam of Hyderabad and was appointed a mansab of high rank, losing the fingers of his right hand in battle with the Marathas. In 1789, Ghulam and his uncle united to defeat Tipu Sultan at the Battle of Tammadapelle on 21st September 1789. After this, Ghulam became ruler of Banganapelle for the second time, but he preferred to live with his family in Hyderabad. He was given additional lands and titles as a marriage gift and also became Jagir of Chenchelimala. He enjoyed a long reign but abdicated in favour of his eldest son in 1822. He died in Hyderabad on 4th June 1825 and was buried at Banganapelle.

Aspects of the tray’s ornamentation such as the eight-pointed star and the turquoise stones hint at the Ghulam’s Persian lineage, where these are frequently found. The most unusual feet may allude to his descendant’s arrival in India during the reign of Emperor Akbar. Akbar was known for his love of elephants and an allegorical painting of the young Emperor riding the elephant Hawa’i in a race, is depicted in a miniature painting in the Akbarnama or Book of Akbar, now in the V & A Museum.

Unusually, the sides of the tray are rolled rather than straight, and finish with a narrow flat rim to the edge. This design maximises the amount of surface available for ornament and allows the repousse ornamentation of the side area to become more visible and flow almost seamlessly as a border to the ornamentation to the flat central area. The most unusual repousse studding to the oval panels is intended, like the stones to the centre, to catch and reflect the light, creating a subtle sparkle and adding to the spectacle.

To the centre of the tray is an eight-pointed star inlaid with foiled glass stones. Around the rim of the tray and to the handles is a single row of oval turquoise stones cut en cabochon. The glorious array of naturalistic birds and flowers of wide variety are typical of Mughal ornament. Here, the plants and flowers are presented in several different ways. The sheer variety of flowers in the scroll border is notable and include jasmine, poppy, iris and narcissus flowers, amongst the many illustrated. The tray is supported by four charming figural feet which show a figure of a young boy balancing on an elephant’s neck.

Maryam Ekhtiar et al explain - ‘The use of complete flowering plants as a decorative motif appears to have had its genesis in works on paper produced during the reign of Jahangir (r. 1605-27). In 1620 the emperor requested that his artist, Mansur, paint the many types of flowers he observed in Kashmir. The three surviving studies by Mansur show such strong affinities with European botanical studies that it is very likely that he and the other Mughal artists who later took up this theme, were using them as a model. Herbals known to have been presented by European visitors to the Mughal court are usually identified as the source of inspiration.’ The flowering plants portrayed on this tray are in the style of Mansur, naturalistically portrayed they also show movement, as if a light wind was gently blowing. As a result of mid-17th century contact between the Mughal and Deccan empires, the Mughal flower style was also adopted in the Deccan.

‘Sometime during the reign of Jahangir’s son, Shah Jahan (r. 1627-1658), the plant studies were transformed into decorative motifs and arranged in rows to cover textiles, carpets, luxury objects and architectural spaces.’ (Ekhtiar et al)

The Taj Mahal mausoleum in Agra, India, was commissioned by Shah Jahan. Construction of the mausoleum began in 1632, after Shah Jahan’s beloved wife, Mumtaz Mahal, had died during childbirth whilst giving birth to their fourteenth child. The principal mausoleum was completed in 1643 with the gardens and ancillary structures completed around 10 years later. The mausoleum features finely carved bas relief marble panels featuring naturalistically depicted flowering plants. It also contains decoratively arched niches, similar in shape to the niche outline which has been used on this tray to frame the flowering plant motif.

A gold tray of similar form but with different, and far less ornamentation, was given to the Prince of Wales, the future King Edward VII, in Mysore, during his four month visit to India in 1876 and there is a photograph in ‘Industrial Arts of India’ (Plate 9). The four-petal flower repeating border shares similarities with the part flowers, alternating with the tops of the oval ‘studded’ panels to the top of the sides on our tray. The Prince of Wales’ tray was exhibited at the Paris International Exposition of 1878 by Lord Northbrook.

| item details | |

|---|---|

| Origin | Asian |

| Period | 18th Century |

| Style | Other |

| Condition | Excellent |

| Dimensions | Weight: 1330 grams |

| Diameter | Height 6 cms; Length 44 cms, Width 25 cms |

Product REF: 10029